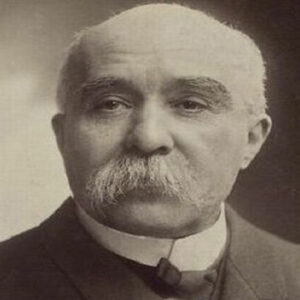

Known by the nicknames “Tiger” and “Father Victory,” Georges Benjamin Clemenceau served as France’s prime minister twice, from 1917 to 1920 and from 1906 to 1909. Like his father, he entered media and politics because of his enthusiasm for Republicanism. Le Matin, La Justice, and Le Bloc, among other newspapers and weekly reviews, were among the powerful tools of Parisian radicalism that he contributed to the field of political journalism. Beginning as the mayor of Paris’s 18th arrondissement in 1870, he later rose to the position of president of the Council of Paris and was chosen to serve in the Chamber of Deputies. His influence on French politics is widely recognized, whether he was the prime minister or the head of the Radical party. He led France through the difficult circumstances of World War I with ease, serving as prime minister for two terms. His conception of human perfection was based solely on morals and scientific knowledge. He took a strong stance and was successful in getting Germany to pay enormous reparations as the senior French delegate to the Paris Peace Conference, where he was instrumental in the formulation of the Treaty of Versailles. Clemenceau was not entirely pleased with the outcome of the Treaty of Versailles due to Germany’s indulgence, despite his partial success. Following his 79-year-old retirement from politics due to his defeat in the 1920s elections, he turned back to writing in order to leave behind his memoirs, Grandeur and Misery of Victory.

Early Life & Childhood

Benjamin Clemenceau and Sophie Eucharie Gautreau welcomed Clemenceau into the world on August 28, 1841, in Mouilleron-en-Pareds, Vendee, Western France.

Benjamin, his non-practicing physician father, was involved in politics. He was well-known for being a supporter of the 1789 Revolution and for having influenced his son’s dislike of Catholicism and pro-Revolution sentiments.

Following his studies at the Nantes Lycee, he received his French Baccalaureate of Letters in 1858.

His father sent him to Paris in November 1861 so he could further his medical studies, and it was there that he met the young people spearheading the republican opposition through the Agis Comme Tu Penses (Act as You Think) organization.

In December 1861, Clemenceau started a publication called Le Travail, or “Work.” Although it covered his next course of action in politics, the cops confiscated it.

He was put in jail on February 23, 1862, as a result of an advertisement he had prepared honoring the Revolution of 1848’s 14th anniversary.

Following his 73-day release, he launched Le Matin (“Morning”), a newspaper that too experienced seizures.

After completing his medical training in 1865, he spent four years in the United States. The Civil War was at its height during this period.

Despite establishing his medical practice in New York, he worked as a political journalist for a Parisian newspaper and dedicated much of his time to literary endeavors opposing Napoleon III’s reign.

He was greatly impacted by American democracy after seeing the freedom of speech and expression, and he grew to respect the officials that supported it.

He began working as a French teacher and riding instructor in a ladies’ school in Stamford, Connecticut, after his father refused to provide him with financial support.

Career

Following the French defeat at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second French Empire, he returned to Paris in 1870. Following his return, he was elected to the National Assembly representing the 18th arrondissement and took office as mayor of Montmartre.

Following the Paris communal’s takeover of power in March 1871, he was unable to broker a settlement between the radical leaders, the communal, and the French government.

Under pressure from the Commune, he was forced to resign from his position as mayor because it was not legally binding.

He made an attempt to succeed with the Paris Commune Council but was not successful. He didn’t get appointed to the Paris Municipal Council until July 23, 1871, in the Clignan court sector, following the Commune’s collapse in 1871. He continued to serve until 1876, holding positions as vice president, secretary, and president in turn.

As a Radical Republican, he was admitted to the chamber of deputies in 1876.In the ensuing ten years, Clemenceau concentrated primarily on journalism.

In 1880, he launched La Justice, a newspaper that came to be seen as the principal tool of Paris Radicalism.

He remained to be at the forefront of French Radicalism despite losing favor since he was a political critic.

Known for his caustic remarks, he earned the nickname “Tiger” for his disruptive involvement in cabinet meetings, including the Ferry Cabinet (1881) with the Tunisian crisis, the Freycinet Cabinet (1855) regarding the Indo-Chinese upheaval, and the Freycinet Cabinet (1881) over Egyptian meddling.

His hatred of the Russian alliance was so obvious that, when he ran for the Chamber of Deputies again in 1893, he was unfairly accused of being on British payroll and charged with complicity in the Panama Canal controversy.

His involvement in the Dreyfus affair, which opposed the anti-Semitic and nationalist efforts, further hampered his career. However, he continued to publish, reaching a total of 665 for Dreyfus’s defense.

Following the closure of his publication La Justice, he founded the weekly Le Bloc in 1900. It ran for two years, ending on March 15, 1902.

On April 6, 1902, he was chosen to serve as a senator for the Var district of Draguignan. He was appointed Interior Minister in 1906 and went on to become Premier. He did everything he could to help Britain and resolve the Moroccan issue.

Following the collapse of his administration in 1909, Clemenceau focused mostly on military readiness for potential conflict.

The Journal du Var, which was initially released in 1910, is credited to him. The publication’s main focus was on foreign policy and the denigration of socialist anti-militarism.

Following his appointment to the Senate’s foreign affairs and army commissions in 1913, Clemenceau founded the publication L’Homme Libre, or “The Free Man.” It focused mostly on German threat and armament.

Despite government criticism that resulted in its banning in 1914, L’Homme Libre was republished as L’Homme Enchainé, or The Enchained Man, which subsequently focused primarily on advancing French victory and exposing any inadequacies on the front lines of combat.

With President Raymond Poincare’s appointment, he resumed his position as premier in November 1917 and held it until 1920.

This time, he accepted the role of Ministry of War. He focused most of his efforts on boosting French morale domestically and popularized the slogan “Je fais la guerre” (I wage war).

He made clear and admirable attempts to establish a unified military command under Ferdinand Foch, and he played a significant role in continuing the war until November 1918.

He was a prominent French representative at the Paris Peace Conference. The principal goals of Clemenceau’s strategy were the disarmament and dehumanization of the Germans and the restitution of the French-lost regions of Alsace-Lorraine from the Franco-Prussian War.

He was at odds with U.S. President Woodrow Wilson mostly because of Wilson’s too idealistic views, which made Clemenceau unhappy with the Treaty.

At the age of 79, Clemenceau lost the January 1920 presidential election due to accusations that he was unduly forgiving of Germany’s behavior during the negotiations of the Treaty of Versailles.

Individual Life and Heritage

Claude Monet, the impressionist painter, has long been friends and confidants with Clemenceau. He was instrumental in securing the transfer of Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies) paintings to the French government, which are currently on show at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

Held in high regard by Clemenceau, who was greatly influenced by the ideologies of Auguste Comte, J. S. Mill, and Charles Darwin, were emancipation and ordinary rights.

He married Mary Eliza Plummer, a student of his at the school, on June 23, 1869, when he was still a teacher at Stamford.

After seven years of marriage, he and Mary Plummer divorced, leaving him with three children—a son and two daughters.

After leaving politics, Clemenceau authored his memoirs, “In the Evening of my Thought,” in 1929.

He spent most of his time writing during his final years, which can be seen in the two volumes of his philosophical testament, Au soir de la pensée (In the Evening of My Thought), which he managed to finish in 1927. He split his time between Paris and the Vendée.

He died in Paris on November 24, 1929.

His chronicle of the war and the Paris Peace settlement, Grandeurs etmisères d’une victoire (Grandeur and Misery of Victory), was released after his death in 1930.

In 1917, James Douglas, Jr. named Clemenceau, Arizona, USA, in Georges S. Clemenceau’s honor.

The French aircraft carrier Clemenceau was named after the 3,658-meter Mount Clemenceau in the Canadian Rockies.

Champs-Élysées – Clemenceau, the 8th arrondissement’s station on lines 1 and 13 of the Paris Métro, bears his name.

Rue Clemenceau honors Georges Clemenceau, a prominent figure in Beirut.

In Singapore, a street called Clemenceau Avenue bears Georges Clemenceau’s name.

Net worth of Georges Clémenceau

The estimated net worth of Georges Clémenceau is about $1 million.