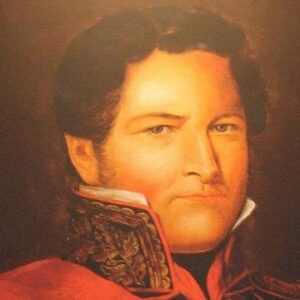

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas was a dictator in Argentina. In the first half of the 1800s, he was in charge of Buenos Aires Province and the Argentine Confederation. He was known as the Restorer of the Law, but in reality, he was a cruel dictator who didn’t let anyone stand in his way. Under him, elections turned into a sham, and the court system became a tool of his dictatorship. Often, people were put to death just to set an example and scare the average people into submission. In fact, he rarely went after the poor. Instead, he shot at people who were already well-known. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t care about his country. It’s just that he always tried to do things his way. For example, he thought that Argentina, which had a large number of people who couldn’t read or write, wasn’t ready for democracy yet and that, for the good of the country, elections had to be rigged. But he couldn’t stay in power for long, and in the middle of the century, he had to leave. He farmed his land in the United Kingdom until the end of his life.

Early years and childhood

Juan Manuel de Rosas was born in Buenos Aires on March 30, 1793. León Ortiz de Rosas, his father, was a military officer and also owned a lot of lands. His mother, Agustina López de Osornio, came from a wealthy family and had a strong will.

The mother had a big impact on Juan, who was the oldest of the couple’s twelve children. He learned his first things at home. He went to a private school when he was eight years old. But he wasn’t a very smart boy, and he didn’t study much. However, he was interested in French absolutism.

In 1806, the British invaded Argentina to take control of the Rio de Plata (River Plate) basin. They stayed in Buenos Aires for 46 days. Juan was 13 years old at the time. Juan was too young to fight directly in the battle, so he was put in charge of getting ammunition to the soldiers.

Even though the British lost this war, they attacked again in 1807. This time, Juan was put in charge of the Caballero de los Migueletes, but there was no record of him going to war. The British were turned back again.

Before the war, the Rosas family lived in Buenos Aires. After the war, they moved to their ranch. Here, he often dressed like the “gauchos” who worked on their estancia, but he never let them forget that he was their boss.

Juan took over the family ranch in 1811, and he and Encarnación Ezcurra were married within two years. He might have started a business because his family didn’t like this relationship.

Juan Manuel’s Career

As Juan Manuel de Rosa, the owner of the land first opened a place for salt meat called Los Cerrillos. His organizational skills and use of nontraditional methods to manage workers helped him get ahead quickly. He then started buying land, and soon he was a landowner on his own.

By this time, the Argentine War of Independence had already started, and all ties with Spain were cut in July 1816. But Argentina which was one country was still a long way off. Over the issue of “provincial autonomy,” there was a civil war between the Province of Buenos Aires and the other provinces. It was really a fight between the Federalists and the Unitarians.

In 1820, Rosas and his gauchos joined the Fifth Regiment of Militia of the Unitarian army of Buenos Aires. Because they wore red uniforms, people started calling them “Colorados del Monte.” They were able to stop the provincial army from getting to Buenos Aires and save the city.

Rosas went back to his estancia after the war. Because the government was grateful for his service, they gave him more land and made him a cavalry colonel. Soon, he built up his own power, and people began to call him a caudillo.

He kept buying more land in the meantime, and by 1830, he was one of the ten biggest landowners in the province. He now owned 420 000 acres and was in charge of a huge army of loyal gauchos.

The First Term as Governor

As Rosas’s power grew, the fight between the Unitarians and the Federalists started to get worse. Even though he used to fight for the Unitarians, he joined the Federalist Party in 1826.

In 1827, he started a revolt against the Unitarian government that had been set up in Buenos Aires. He did this because he thought that the policies of the government were bad for Buenos Aires. He thought that the Federalists, which supported independence for each province, would be good for the province.

In the same year, Rosas was a big part of making Manuel Dorrego, a leader of the Federalist Party, the governor of Buenos Aires. In return, Rosas was put in charge of the rural militia as its General Commander. It made him even more influential.

In 1828, a group of Unitarians killed Dorrego. This left a hole in the leadership of the Federalists. Rosas jumped in right away to fill the empty spot.

He then joined forces with other powerful caudillos and, at the Battle of Márquez Bridge in April 1829, beat the Unitarian leader Lavalle. In November 1829, he arrived in Buenos Aires with a warm welcome, and on December 6, 1829, the House of Representatives of the province chose him to be Governor.

Rosas will bring order to the chaos next. But it wasn’t a simple job. The Unitarians had not yet been completely ruled over. His government also took over with a big budget deficit. At the same time, the country was going through a very bad drought.

To help solve the financial problems, he focused on getting more money in and spending less. Using the amazing power that was given to him, he also shut down the press and sent his enemies away. In the end, the main Unitarian leaders were caught in 1831, which put an end to the Civil War.

Rosas was given credit for keeping the country from being both politically and economically unstable, but some of the Federal leaders started to ask for a constitution. Rosas didn’t want to be tied down by the law, so when his term was over on December 5, 1832, he went back to running a ranch.

The second term as governor

Rosas led an expedition to the south of Argentina in 1833. At the time, the Indians were in charge of that area. It was called the “Desert Campaign,” and it lasted for two years. When it was over, the Indians had been defeated, and the land was free for more white settlements.

While he was away fighting in the Campaign, his followers, who were called “Rosistas,” became a powerful part of the party. They told other groups that the only way to get the country back to normal was for them to accept Rosas as governor and give him full power.

So, on March 7, 1835, Rosas was re-elected as Governor, but this time he had full control over the province of Buenos Aires. Not only did the Rosistas trust him, but so did the ranchers, businessmen, and Catholic clergy. A rigged poll got rid of those legislators who were against him.

Rosas set up a totalitarian government. He was in charge of every part of government and treated his ministers like they were his secretaries. His backers were given good positions, and anyone who was seen as a threat was killed without mercy. Terrorism by the government was the norm.

From 1829 to 1852, state police killed about 2,000 people, according to a rough estimate. Many more people were hurt by them. Tongues were often cut off and males were castrated. The police also drove through neighborhoods and looked through people’s homes just to scare them. Many people in Argentina left because they were afraid for their lives.

At the same time, Rosas started to build a cult of personality around himself and show himself as an all-powerful guardian of the country. Portraits of him were put on church altars and other public places at his request. People had to wear red, which was the Federalists’ sign, as part of what they wore. Red was also used to paint the houses.

His Argentina leader

Even though the government used terrorism, there were sometimes uprisings. When former governor Juan Lavelle came back from exile in 1839, it was the worst of them all. With the help of French weapons, as many as five provinces joined together to attack Buenos Aires.

Rosas was lucky that the British came to his aid, but the battle was still tough. In December 1842, Lavelle was killed, and all provinces except Corrientes were put under control. In 1847, the latter was finally put down.

Very soon, he was in charge of the whole country. By 1848, he started calling his government the Confederate Government and himself “The Supreme Head of the Confederacy.”

Rosas had always thought that Uruguay and Paraguay were parts of Argentina that had gone against the government. After getting stronger at home, he attacked Uruguay in 1843 and took over a lot of the country. He even ignored blockades from England and France and kept control of that countries.

Rosas’s defiance made him popular, but he didn’t notice that Argentines were getting more and more unhappy. Justo José de Urquiza, who was one of his most trusted lieutenants, began to want to replace Rosas. Even Rosas, who lived alone in a house in Palermo that was heavily guarded, didn’t know that.

Justo José de Urquiza, Brazil, and Uruguay got together to form a coalition. In the next war, the Plate War, which started in 1852, the Argentinean army had to admit defeat, and Urquiza led a group of rebels on a march toward Buenos Aires.

Rosas now knew he had lost, so he went quietly to England on a ship. He was a farmer for the rest of his life in that country. Back home, he was tried without him being there, and all of his property and records were taken away and destroyed.

Personal History and Legacies

Rosas married Encarnación Ezcurra on March 16, 1813. She was an important part of Rosas’s career, and her husband probably trusted her more than any other lieutenant. Juan Bautista was their son, and Manuela was their daughter. Both of the children went with their father when he was sent away.

In England, Rosas worked on a farm as a renter and had a pretty good life. He died of pneumonia on March 14, 1877, and was buried in Southampton. He was the most hated person in Argentina at the time. Later, a movement called “Revisionism” tried and failed to change how people saw him.

In the 1980s, he tried again to improve how people saw him. In 1989, his body was brought back to Argentina and buried in a family vault. His picture also started to show up on banknotes and stamps. He is now remembered by a monument and a train station.

Estimated Net worth

Unknown.