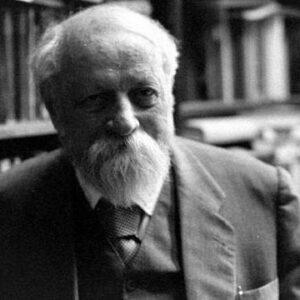

Martin Buber was a prominent twentieth-century Jewish philosopher, exceptional religious thinker, political activist, educator, essayist, translator, and editor whose ‘philosophy of dialogue’ re-defined theological existentialism. Martin Buber was born in Austria, but he lived much of his life in Israel and Germany. Through his study of Hasidic Judaism, Buber was a cultural Zionist who championed the cause of Jewish cultural renewal. Through his writings, he attacked Kant, Hegel, Marx, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Dilthey, Simmel, and Heidegger’s works, and he was a huge influence on Emmanuel Lévinas. Buber and Franz Rosenzwig co-wrote a number of religious and Biblical studies as well as translated the Bible from Hebrew to German. Buber was a pioneering adult educator who founded Jewish education institutes in Germany and teacher-training centers in Israel, as well as developed the theory of character education. In the biography below, learn everything there is to know about Martin Buber’s life and accomplishments.

Childhood of Martin Buber

Mordecai Martin Buber was born in Vienna on February 8, 1878, to Elise née Wurgast and Carl Buber, an orthodox Jewish couple. He couldn’t stay with them for long, though, because his parents divorced in 1882. Buber spent the next ten years of his life with his paternal grandparents, Solomon and Adele Buber, in Lumberg (now Ukraine).

Solomon was a big inspiration for tiny Buber because he was a communal leader and a well-known Jewish theological expert. He was also acknowledged by ultra-orthodox organizations for publishing the first modern editions of rabbinic Madras literature. Martin’s grandfather exposed him to Jewish ideology and taught him Hebrew. This sparked an interest in Zionism and Hasidic literature in him. He, too, was enthralled with the Kabbalah School of Thought. He was strongly touched by the idea that people could grasp God by thinking faithfully.

Education of Martin Buber

Martin’s grandparents were wealthy, and they owned the Galician estate which enabled them to fund Martin’s education. Their financial backbone was broken, however, when the estate was confiscated during World War II.

Buber, who was home-schooled and spoiled by his grandmother, grew up to be a ‘bookish aesthete’ with few peers his age. He quickly learned Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish, and German in addition to Greek, Latin, French, Italian, and English at home. At home, he spoke German, and at the Franz Joseph Gymnasium, he was educated in Polish. Buber’s life-long obsession with words and meanings was sparked by his multilingualism.

A Watershed Moment

He turned away from Jewish religious rituals due to a personal theological crisis, and he became absorbed in the books of Immanuel Kant, Soren Kierkegaard, and Fredrich Nietzsche. As a result, he decided to major in philosophy during his university years. In the year 1898, Martin Buber took part in the Congresses and its organizational activities. In the next year, while studying in Zurich, he met his future wife, Paula Winkler, a non-Jewish Zionist writer. She was born in Munich and converted to Judaism later in life. Buber studied art history and philosophy as a university student at Leipzig, Zurich, Berlin, and Vienna. Buber enjoyed reading classic German idealism and romance from the nineteenth century. Friedrich Nietzsche, Soren Kierkegaard, and Fyodor Dostoevsky all influenced Buber’s philosophic concepts. In 1904, Buber received his Ph.D. for his thesis on German mysticism.

The career of Martin Buber

In the year 1900, Buber and his wife Paula Winkler moved to Berlin, where he stayed with his close friend and anarchist Gustav Landauer (1870-1919). Martin, Paula, and their two children left the big metropolis in the same year and relocated to Heppenheim, a tiny town near Frankfurt, where Martin worked as an editor. Landauer chastised Buber in 1916 for his public support for the German war effort. Martin was transformed from an aesthetic spiritual social figure to a philosopher of conversation. Martin met Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929) at this time, with whom he had a close intellectual partnership. Martin was hired as a lecturer at the newly founded Jewish adult education center (FreiesjüdischesLehrhaus) after the war ended. Buber agreed to give thorough lectures on Jewish religious studies and ethical concerns in Frankfurt after Rosenzweig persuaded him. Martin was led by Rosenzweig, who served as the project’s Chief Collaborator. The project was started by Lambert Schneider, a young Christian publisher on a quest to produce a new German translation of the Bible in Hebrew. He worked in Frankfurt until 1937 when he relocated to Palestine. He spent the rest of his life in Jerusalem, where he taught social philosophy.

Zionist Points of View

When he said Zionism, Theodor Herzl did not take into account Jewish religion or culture, which was in direct opposition to what Buber believed. Instead, Buber believed that Zionism was for the betterment of society and religion. Buber became interested in the Jewish Hasidic movement a year later. He was hired as the editor of ‘Die Welt,’ a weekly that served as the Zionist Movement’s major publication. Martin Buber admired the Hasidic communities’ dedication to their religion in their daily activities. Despite their political worries, Hasidim stood firm in their ideals, which Buber had hoped Zionists would follow. Buber later withdrew from Zionist organizational work in 1904 and focused his energy on learning and writing. ‘Beiträge zur Geschichte des Individuationsproblems’ (on JakobBöhme and NikolausCusanus) was one of numerous theses he published in the following years.

Academic Profession

Between 1910 and 1914, Buber immersed himself in the study of published editions of mythological texts. After that, in 1916, he relocated from Berlin to Heppenheim. During World War I, Buber established the Jewish National Commission in an attempt to better the situation of Eastern European Jews. Martin Buber penned ‘Ich und Du,’ a famous essay that was eventually translated into English as ‘I and Thou,’ in the year 1923. He denied making significant changes to the essay, despite the fact that he had edited it. Later, in 1925, he collaborated with Franz Rosenzweig on a project to translate the Hebrew Bible into German. He coined the term “Germanification” to describe the process because the words that were replaced were not intended to be solely German, but rather to be an equivalent to the meaning of the sentence in the Hebrew original. ‘Die Kreatur’ is a German word that means “creation.” Buber co-edited The Creature, a quarterly, from 1926 to 1930.

Buber as a Professor

In 1930, Buber was appointed as an honorary lecturer at the University of Frankfurt am Main. He resigned from his employment in 1933 as a form of protest against Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. In 1933, the Nazi authorities exempted him from giving lectures and dismissed him from the Reichsschrifttumskammer, the National Socialist authors’ society. In response, Buber established the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which provided Jews with public education, a vital entitlement that had been taken away from them. The Nazi authorities, on the other hand, did not approve of it and outlawed this body. When nothing seemed to be going his way, Buber moved to Jerusalem in 1938 to work as a professor at the Hebrew University, where he gave anthropology and sociology lectures. He took part in debates on the Jewish community’s problems in Jerusalem. Martin Buber became a member of the ‘Ichud’ movement in Palestine, which intended to create a bi-national state for Arabs and Jews. He achieved a lot more oriented relief towards the fulfillment of Zionism rather than the attainment of a single state as a result of this. In 1946, he published ‘Paths in Utopia,’ which contained his communitarian socialist beliefs and conceptions of interpersonal dialogical connections.

Philosophical Perspectives

Martin Buber was significantly impacted by Kant’s ‘Prolegomena’ and Nietzsche’s ‘Zarathustra’ when he was fourteen years old. After Buber graduated from Gymnasium, Nietzsche’s impact faded, while the prophetic tone of Nietzsche’s writings remained. In Vienna, Berlin, Leipzig, and Zurich, he studied art history, German literature, philosophy, and psychology. He accepted the most modern literature and poetry while in Vienna, particularly Stephan George’s poetry, which he was highly affected by, albeit he did not become George’s pupil.

Death of Martin Buber

Martin Buber died in June 1965, and the New York Times called him “the leading Jewish religious thinker of our time and one of the world’s most prominent philosophers” after his death.

Recognition & Awards

Goethe Award, University of Hamburg; German Book Trade Peace Prize, 1951; Israel Prize in the Humanities, 1953; Bialik Prize for Jewish Thought, 1958; Erasmus Prize in Amsterdam, 1961; Goethe Award, University of Hamburg; Goethe Award, University of Hamburg; Goethe Award, University of Hamburg; Goethe Award, University of Hamburg; Goethe Award, University of Hamburg; Goethe Award

In 2005, he was voted the 126th greatest Israeli of all time (in a poll by Israeli news website)

Work

The Legend of Baal Shem, (Die Geschichten des Baal Shem), 1906 The Tales of Rabbi Nachman, (Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman), 1906 (Die Legende des Baal Schem ), 1911a Three Speeches on Judaism, (Drei Reden über das Judentum), 1911b The Jew. A Monthly, (Der Jude. A Monthly), 1908 Chinese Ghost- and Love Stories, (Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten), 1911a Three Speeches on Judaism, (Drei Reden über das Judentum), 1911b The Jew. A Monthly, (Der Jude. a monthly publication) 1916-1924

Recollections of my journey to Hasidism (Mein Weg zum Chassidismus. Erinnerungen), Der heilige Weg. A Word to the Jews and Gentiles (Der heilige Weg. A Word to the Jews and Gentiles) (Der heilige Weg. A Word to the Jews and Gentiles) (Der h A word to the Jews and the Germans), 1919

The Succession of the Great Maggid (Der grosse Maggid und seine Nachfolge), 1924

Both I and you (Ich und Thou), 1923 Das verborgene Licht, 1924 Creation, 1926- 1929

Legacy

Nahum Glatzer (Buber’s only Ph.D. student during his term of study at the University of Frankfurt, 1924-1933), Akiba Ernst Simon, and others took up Buber’s work in the continuation of Buber’s work (an education historian as well as a theorist in Israel who met Buber at first at Freiesjudisches Lehrhaus in Frankfurt).

Martin Buber’s Net Worth

Martin is one of the wealthiest philosophers and one of the most well-known philosophers. Martin Buber’s net worth is estimated to be $1.5 million, according to Wikipedia, Forbes, and Business Insider.