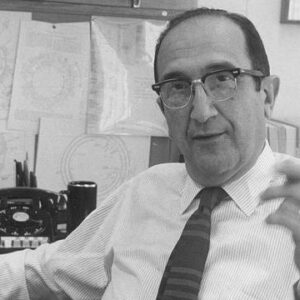

Salvador E. Luria was an Italian microbiologist who, with Max Delbrück and Alfred Hershey, shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1969 for his discoveries on the replication process and genetic structure of viruses. He was born into an influential Jewish family in Turin, Italy, and attended medical school at the University of Turin before serving as a medical doctor in the Italian army for a while. He subsequently went on to the University of Rome to study radiology, where he became interested in bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria). He obtained a fellowship to study in the United States as a brilliant student. Benito Mussolini’s fascist administration in Italy at the time prohibited Jews from receiving academic research funds. He moved to Paris, France, frustrated. The Nazi German army invaded France in 1940, compelling Luria to flee to the United States during a period of political turmoil in Europe. He continued his research in the United States and soon met Delbrück and Hershey, with whom he conducted numerous experiments, including the Nobel Prize-winning work. He finally became an American citizen by naturalization. Luria was an active political campaigner who opposed the war and nuclear weapon testing throughout his career.

Childhood and Adolescence

Salvatore Edoardo Luria was born on August 13, 1912, in Turin, Italy. Ester (Sacerdote) and Davide Luria were born into a powerful Italian Sephardi Jewish family.

He attended the University of Turin’s medical school, where he met two other future Nobel laureates, Rita Levi-Montalcini and Renato Dulbecco. In 1935, he received his M. D. summa cum laude.

He was a medical officer in the Italian Army from 1936 to 1937, after which he went to the University of Rome to study radiology. He became interested in bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria—and did genetic theory experiments on them while he was there.

He was awarded a fellowship to study in the United States in 1938. At the time, Italy was wracked by Benito Mussolini’s fascist administration, which barred Jews from receiving academic research fellowships.

Luria left Italy for Paris, France, frustrated at being denied this opportunity. In 1940, the chaotic situation in Europe worsened as Nazi German soldiers invaded France. Luria had no choice but to depart France. He was fortunate enough to be granted an immigrant visa to the United States.

Salvador Luria’s Career

His name was changed to Salvador Edward Luria after he arrived in the United States. He knew Enrico Fermi, a physicist who assisted Luria in receiving a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship at Columbia University.

During his research, he met Max Delbrück and Alfred Hershey, and the three collaborated on experiments at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and Delbrück’s lab at Vanderbilt University.

Delbrück connected Luria to the American Phage Organization, an informal scientific group focused on viral self-replication research. While working with a member of the group, Luria was successful in acquiring one of the electron micrographs of phage particles.

Luria and Delbrück created a highly productive professional partnership. In 1943, they conducted the Luria–Delbrück experiment, which revealed that genetic changes in bacteria occur in the absence of selection rather than as a result of selection.

He worked at Indiana University as an Instructor, Assistant Professor, and Associate Professor of Bacteriology from 1943 until 1950. In January 1947, Luria became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Professor of Microbiology at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, he was appointed in 1950. He discovered in the 1950s that an E. coli culture may considerably inhibit the formation of phages produced by other strains.

In 1959, he assumed the Microbiology Chair at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He moved his study focus from phages to cell membranes and bacteriocins in his latter years and discovered that bacteriocins hinder cell membrane function by producing holes in the membrane.

He was named Sedgwick Professor of Biology at MIT in 1964, and chair of The Center for Cancer Research at MIT in 1972.

Throughout his career, he has been a vocal opponent of nuclear weapons testing and a critic of the Vietnam War. Because of his political activity, he was temporarily barred from obtaining funds from the National Institutes of Health in 1969.

‘Journal of Bacteriology,’ ‘Journal of Molecular Biology,’ ‘American Naturalist,’ and ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’ were among the periodicals where he served as Editor or Member of the Editorial Board.’ He also wrote ‘General Virology,’ a college textbook, and ‘Life: The Unfinished Experiment,’ a popular text for the general reader (1973).

Luria’s Major Projects

He produced key discoveries on the replication mechanism and genetic structure of viruses while working with Delbrück, and showed that bacterial resistance to viruses (phages) is genetically inherited. Luria also demonstrated that spontaneous phage mutations exist.

Achievements and Awards

In 1969, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared by Salvador E. Luria, Max Delbrück, and Alfred D. Hershey “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.”

In 1969, the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize for Biology or Biochemistry was shared by Luria and Delbrück.

In 1991, he was awarded the National Medal of Science.

Personal History and Legacy

In 1945, Salvador E. Luria married Zella Hurwitz. His wife was a psychology professor at Tufts University. Daniel, their only child, went on to become an economist.

On February 6, 1991, at the age of 78, he died of a heart attack.

Estimated Net worth

Salvador is one of the wealthiest geneticists and one of the most well-known geneticists. Salvador Luria’s net worth is estimated to be $1.5 million, according to Wikipedia, Forbes, and Business Insider.