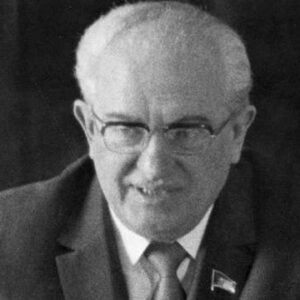

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s fourth general secretary was Yuri Andropov. After becoming an orphan at the age of 13, he worked odd occupations throughout his teenage years. At the age of 16, he joined the Komsomol. At the ages of 22 and 24, he served as the organizer of the Volodarsky Shipyards Komsomol Central Committee and the First Secretary of the Yaroslavl Regional Committee of the Komsomol. He joined the Communist Party when he was 25 years old and was assigned to the CPSU Central Committee staff when he was 37. He was named Russian Ambassador to Hungary when he was 40 years old, and during the 1956 uprising, he played a crucial role in the Russian invasion. He was 53 years old when he was elected as a candidate member of the Politburo and appointed head of the KGB. He held the latter position for 15 years while brutally suppressing descent. In the interim, he became a regular member of the Politburo and gradually rose to a place of prominence within it. After Leonid Brezhnev, the third General Secretary passed away in 1982, he eventually took over. V only served in government for 15 months before passing away at age 69 from renal failure.

Young Adulthood & Youth

On June 15, 1914, Yuri Andropov was born in Nagutskaya, a railroad stop in the Russian Empire’s Stavropol Region. It is currently a component of the Russian Federation’s Federal District for the North Caucasus.

From a wealthy Don Cossack household, Vladimir Konstantinovich Andropov was a railway official. His mother, Yevgenia Karlovna Fleckenstein, was of Finland and German ancestry and was the daughter of a Moscow watchmaker.

Yuri Andropov was the sole offspring of his parents. When he was still very young, his father passed away from typhoid. After that, his mother followed him to Mozdok, where she later remarried. His parents were divorced, according to some other accounts.

Yuri was only thirteen years old when his mother passed away in 1927. After that, his stepfather Viktor Aleksandrovich Fedorov reared him, and at the age of 14, he sent him to work. He completed his education at the same time.

Before joining the Komsomol

Andropov spent his adolescent years working for the Volga steamship line as a loader, telegraph operator, cinema projectionist, and sailor. He joined the All-Union Leninist Youth Communist League (YCL), also known as the Komsomol, in 1930 while still living in Mozdok.

He enrolled in Rybinsk Water Transport Technical College sometime in the early 1930s to pursue water transport engineering. Meanwhile, he kept up his political involvement and ultimately rose to the position of full-time secretary of the college’s Komsomol unit.

Andropov earned his degree as a water transport engineer from Rybinsk Water Transport Technical Institute in 1936. He then joined the Volodarsky Shipyards in Rybinsk and was given the opportunity to advance to the position of Komsomol Central Committee Coordinator, which required him to work extremely efficiently.

He was employed by the Volodarsky Shipyards for a brief time, but it was long enough for his superiors to take note of his effectiveness. He was chosen as the first secretary of the Komsomol’s Yaroslavl Regional Council in 1938. He joined the Communist Party the following year.

He was appointed First Secretary of the Komsomol Central Committee in the newly established Karelo-Finnish Autonomous Republic in 1940, and he held that post until 1944. He also oversaw a band of rebel guerillas operating in Finish Army-controlled territory during this time.

Having a job with the Communist Party

Organizing the youth in the Karelo-Finnish area fell to Andropov in 1944 as he became more involved in the Communist Party. He ultimately received a promotion to a position as a Soviet supervisor in the same area.

He enrolled in the University of Petrozavodsk in 1946 and worked for the Communist Party while also pursuing philology there until 1951. In the meantime, in 1947, he was chosen to serve as the Second Secretary of the Central Committee of the Karelo-Finnish SSR Communist Party.

His transfer to Moscow in 1951, where he was assigned to the CPSU Central Committee, a place regarded as a training ground for promising young officers, marked a turning moment in his life. Here, he was initially given the position of investigator before rising to lead a Central Committee division.

Representative in Hungary

Up until 1953, Yuri Andropov stayed in Moscow. He was a good candidate for advancement in the post-Stalin era because the majority of his superiors were staunch Stalinists and despite the fact that he served them with great loyalty, he was never connected to the terror the secret police spread during that time.

Andropov was appointed to the Soviet Diplomatic Service not long after Stalin’s demise on March 5, 1953. He was sent to Hungary, then a Soviet satellite state, in the same year after completing a brief training program in Moscow. He began his career as a diplomat at the Budapest-based Soviet Embassy.

He was named Soviet Envoy to Hungary in July 1954. He closely followed the developments leading up to the Hungarian Revolution in October 1956 over the course of the following two years, reporting frequently to Moscow and helping to put an end to the rebellion.

The Soviet Union’s first secretary of the Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev, was initially hesitant to attack Hungary. Erno Gero, the first secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party, sent a cabled request for Soviet military aid, which helped Andropov persuade him that a military invasion was required.

Additionally, by misinforming Imre Nagy, the prime minister of Hungary, about Soviet intentions, he was able to persuade him that he was safe. In the end, the USSR attacked Hungary in November 1956 and brutally suppressed its descent. Nagy was ultimately apprehended and killed in 1958.

Chief of FSB

Andropov returned to Moscow in 1957 and served as director of the department for liaison with the Communist and Workers’ Parties in socialist nations until 1967. He joined the CPSU Central Committee as a full member in 1961 and was elevated to its Secretary the following year.

He was appointed a Prospective Member of the Politburo in 1967. On the recommendation of Mikhail Suslov, the Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR, he was named Chairman of the Soviet secret police, the KGB, in the same year.

He had two key responsibilities when he assumed the role. First and foremost, he needed to rebuild the KGB’s reputation after Stalin and his allies severely damaged it. Second, he needed to quiet critics who had been calling for more de-Stalinization and openly denouncing violations of human rights.

For 15 years, Andropov presided over the KGB as its head, transforming it into one of the most effective secret police agencies in the entire globe. He organized efforts to restore its reputation among the populace while also taking care to stop its officials from abusing their positions of authority for personal gain.

He began restoring the KGB’s reputation and trying to put an end to dissent. He created the Fifth Directorate of the KGB in July 1967 with the intention of eradicating all opposition. He thought the fight for human rights was a plan by the imperial powers to replace Soviet doctrine.

He advocated for the execution of dissenters in 1968 who had been detained and condemned to years of hard labor for spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. Some received drug treatments at psychiatric institutions after being admitted. Still, more people received lifetime banishment.

Andropov suggested drastic action when a liberalization campaign started in Czechoslovakia in January 1968. He started a false propaganda campaign, alleging that NATO was attempting to undermine the nation. His contributions were swiftly acknowledged, and in 1973 he was elected as a complete Member of the Politburo. He continued to lead the KGB and made a name for himself as a capable and trustworthy commander. By the end of the decade, he had ensured that all organizations agitating for individual freedom and human rights had been subdued.

Andropov started positioning himself as General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev’s replacement in the middle of the 1970s as his health started to deteriorate. He opposed the USSR’s choice to invade Afghanistan in 1979 out of concern that the USSR would be held accountable by the international community. He was later shown to be correct.

He was effective in convincing General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev not to send troops or launch an invasion of Poland in 1981 when the Solidarity Movement in that country was just getting started. He also made an effort to support reform-minded politicians during this time, Mikhail Gorbachev being one of them.

The Soviet Union’s premier

Andropov left the KGB in May 1982 in order to join the Politburo. He was chosen by the Communist Party Central Committee to serve as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on November 12, 1982, two days after Leonid Brezhnev passed away.

The Western World did not at all warmly embrace his appointment. He was the subject of numerous stories in the Western mainstream media, the majority of which were critical of him. He was viewed as a fresh danger to global security, particularly in Western Europe and the USA.

Andropov started his anti-corruption crusade not long after winning the election. He had gathered enough evidence during his tenure as KGB chief to demonstrate pervasive corruption in the government. Using the secret police to track down the offenders, he fired 37 first secretaries and 18 ministers while also launching numerous criminal investigations against many of them.

He also made an effort to revive the economy by increasing efficiency while maintaining communist principles. He began a program that rewarded productivity and penalized absenteeism in order to increase industrial output. Young officials were also nominated by him to the Politburo.

In terms of foreign policy, he started looking into methods to leave Afghanistan. Additionally, he began Soviet-American arms control negotiations over intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe as part of a peace drive. His goal was to prevent the USA from stationing Pershing weapons in Western Europe.

He announced that the Soviet Union had stopped all development of space-based missiles in August 1983. However, in September, he defended his frontier forces and strained relations with the West when his soldiers shot down a Korean airliner that had inadvertently entered Soviet airspace.

Intermediate-range nuclear weapons arms control negotiations in Europe were put on hold in November 1983, and the Soviet Union quickly retreated entirely. His health had significantly declined by that point, and he had begun conducting business from a hospital.

Personal Influence & Life

Nina Ivanovna, whom Yuri Andropov may have known from his early years, was his first wife. Evgenia Y. Andropova, a daughter, was born to the pair in 1936, and Vladimir Y. Andropov, a son, in 1940. Vladimir passed away in 1975 for an unknown reason. The pair split up in the 1940s.

Sometime in the 1940s, Andropov wed Tatyana Filipovna, his second wife. On the Karelian Front, where she served as the Komsomol secretary, they had first met during the Second World War. They had two kids: Igor Y. Andropov, a boy, was born in 1941, and Irina, a daughter, was born in 1946.

Andropov experienced complete renal failure in February 1983. He was moved to the Central Clinical Hospital in western Moscow in August, where he remained until his passing on February 9th, 1984. He was sixty-nine years old at the time.

Estimated Net Worth

Unknown.

Trivia

There was a persistent claim that Yuri Andropov was of Jewish ancestry due to the maiden name of his mother. However, it proved to be untrue. It has since been established that a significant number of Religious Germans also bore the surname Fleckenstein.

Andropov got a letter from Samantha Smith, a 10-year-old American girl, while he was still in office. She voiced her concern about a nuclear conflict between the US and Russia in it. Andropov took the time to personally respond and reassure her that his nation did not intend to initiate a nuclear conflict.

At her husband’s burial, Tatyana Filipovna Andropova made her first public appearance. She was so overcome with sorrow that her family members had to assist her in walking. Before closing the coffin’s top, she gave him two kisses. She later recited a love poem written by her spouse in a 1985 documentary.